Mohsin Hamid: Moving on

by Mark Reynolds

“A masterpiece… a beautiful book.” Michael Chabon

Mohsin Hamid’s latest novel Exit West imagines a world in which war refugees and economic migrants have the chance to break for safety by passing through supernatural black doors that serve as wormholes to wealthier countries. It’s a magical conceit that fast-forwards the likely exoduses of the coming decades, and intensifies the human dramas of striking out for a new life in a strange land. The story begins in an unnamed city with a swollen population on the brink of civil war, where a young couple, Saeed and Nadia, come together and relocate first to Mykonos, then on London and San Francisco, meeting fellow migrants from other lands and confronting new challenges and freedoms along the way. It’s a short, intense, imaginative, sympathetic and ultimately hopeful portrait of broken societies and their potential correctives.

MR: All your novels are compact and finely honed. Do you start with a broader canvas and cut back to this kind of length, or do you always plan to keep things brief?

MH: I have cut back earlier with some of my books, but in this case and with my last one I didn’t. I think I’m naturally attracted to the idea of a book you can read in one sitting: you start reading in the afternoon and by dinnertime, or before you go to bed, you’ve finished. I just gravitate towards it.

Does that reflect your own reading habits?

I read big books, but I proceed very slowly. In modern life there’s so much distraction, so many things competing for our attention, that when I find a novel I can consume in one or two or three nights, I really enjoy that experience, and I guess it’s what I try to do myself.

An allegorical tone is set by formal, sometimes archaic language, and some of the long single-sentence paragraphs have the authority of Biblical passages. Take away the smartphones and the portals, and this could be a snapshot of any time in human existence, past, present or future.

Yes, there is a timelessness to the story. In terms of those long passages, I thought of it as a kind of incantation or prayer, in the voice of a priest, a witch doctor or magician, whatever you want to call it. It accretes throughout the novel. Like in music, there’s a structure that you build up, and once you’re used to a kind of refrain, then improvising around it is more palatable. So by the time the very long sentences towards the end of the book are appearing, it’s a mode that you’re in as a reader. But the sentences are guided by your ear, not your eye. Even though there aren’t a lot of full stops, there are places to rest along the way. It’s not meant to be in any way baffling or challenging to the reader, it’s meant to serve as a kind of rhythmic inevitability.

Is there an audiobook?

Yes there is. In the UK they usually have an actor do it, in the US they usually have me do it, so depending on which you want to listen to, both are available.

Is it trickier to say out loud than it is to read on the page?

It is, although probably half my writing day is spent reading my stuff out loud. I print out whatever I’m working on, and I pace around in my study reading it. I do that at least as much as I’m actually typing into my keyboard. But reading by myself, as though I’m delivering a soliloquy, is one thing, reading to an audience that is actually there is another thing, and both work equally well. But for an audiobook you’re reading for an audience that isn’t there, your imagining that audience but you’re in a studio with a sound engineer, and I find it much more challenging. I expect it’s the same for actors: rehearsing by yourself is one thing, being on stage is something else, but having a camera shoved in your face and trying to pretend to be in love or frightened must be very, very difficult indeed. At least for me, the audiobook version feels like that.

Most people don’t cross the Mediterranean in a dinghy or trek from the Balkans up to Germany. But preparing to leave and being somewhere else are something so many of us experience.”

The novel switches about halfway in from the effects of war on Saeed and Nadia’s homeland, to an examination of dislocation in a globalised world, both for them and for other characters. Was that dichotomy deliberate from the start, or did it emerge organically?

Well, there’s part of the novel where they haven’t yet passed the door, and there’s part of the novel after they have passed the door: there’s what leads us to move and what we have to overcome and give up to move, and then the aftermath. So yes, the novel has two different modes. Once you’ve left a place that you’ve grown up in for somewhere else, suddenly the world gets a lot bigger, and they see a much bigger world out there.

Gated house with piped water in a refugee settlement in Herat, Afghanistan, November 2009. Sustainable Sanitation Alliance/Wikimedia Commons

Why did you choose to create these surreal portals to safer lands rather than describe the hardships of a physical journey across borders?

While obviously in the lives of real refugees or migrants those journeys are tragic and narratively interesting, I think so little of the experience of migration is to do with the movement of people. I wanted to not focus on that part of the story, which is the part we so often focus on, because that’s where the migrant is so different from anybody else. Most people don’t cross the Mediterranean in a dinghy or trek from the Balkans up to Germany on foot with their possessions on their back. But the other two parts, preparing to leave and being somewhere else, are something so many of us experience. I also wanted to compress the next century or two of human migration in to a year, and the portals allow that to occur as well.

As they are about to leave, Nadia reflects: “When we migrate, we murder from our lives those we leave behind.” For her this is almost a point of principle, whereas for Saeed it’s a cause for regret, and that’s one of the reasons they begin to splinter. He clings to the familiar and is homesick for his roots, while she resolutely embraces the new…

Yes, I think that’s right. Saeed has a past he thinks of as wonderful, and wishes to keep elements of it with him, emotionally but also in terms of the people and the places. Nadia looks to the future with much less nostalgia and more of a sense of potential, and so they do have a fundamentally different relationship to moving. Also they’re quite different as people. Oftentimes if you’ve met someone on a summer holiday, or in some sort of dramatic situation, couples that might otherwise not form, get formed. And for Saeed and Nadia it’s unclear, if what befalls the city hadn’t happened, whether they ever would have got together. But the couple is forged in that context, and then when it moves from that context it’s subjected to all kinds of tensions.

I’m not saying that nations need to be abolished, but I think a great deal of thought has to go into the issue of what is larger than the nation and what is smaller than the nation.”

As the exodus through the doors begins, you write: “Without borders nations appeared to be becoming somewhat illusory, and people were questioning what role they had to play.” Why is the questioning of nationhood important?

There’s nothing eternal about the concept of nations. It’s a relatively new concept, the nation state. We had tribes and we had multi-ethnic empires and all kind of things in between. At this particular moment so many of our problems are either local or global. A level below the nation state is where we address our schools and our traffic congestion and our police forces, and a level way above the nation is where we have to address climate change and epidemics and economic regulations. So the nation state is caught in the middle, and where it tries to do things it can’t do, or can’t do well, it can become counterproductive. Borders are becoming more permeable. The tendency I think we’re beginning to see is that the unquestioned nation state, the nation state that’s trying to reassert a primacy that it is perhaps no longer entirely suited for, in its attempt to make us safe, and its inability to do so many of the things that are needed to make us safe, threatens to become a prison, a society in which there’s the utmost of surveillance and the minimum of due process, a kind of police state where everybody’s watched and where basic notions of civil rights are being trampled on. I’m not saying that nations need to be abolished, but I think a great deal of thought has to go into the issue of what is larger than the nation and what is smaller than the nation. To a certain extent, smaller-than-the-nation thinking is already happening, whether it’s devolution towards regions, regions seeking independence, or city governments taking on more power. But above the level of the nation we’re seeing so little, and we probably need to see much, much more.

As I mentioned, there are glimpses into other lives dotted through the book, including those who cross through the portals out of curiosity rather than severe need. Why did you want to introduce those vignettes?

They are about different experiences of migration: being a person in a place to which large numbers of migrants are coming; being someone who migrates on holiday or for a couple of years; being someone who never migrates, who remains is the same place and still experiences a sense of migration because the place itself changes over time. I wanted to examine all those different forms of migration and see if we can find common human threads that go through them, so that the notion of some people being migrants and some not is questioned. Because I think everybody is a migrant.

As the old woman who has lived in Palo Alto all her life observes, “We are all migrants through time.” What can we learn from that realisation?

Well, many of the political movements that are powerfully nostalgic in the West have disproportionate support from older people. Younger people supported Bernie Sanders, older people support Donald Trump; younger people supported Remain and older people supported Brexit. Not exclusively, but to a meaningful degree there was a difference, and I think a lot of that political nostalgia comes from being unable to visualise a hopeful future.

You talk about a “plausible desirable future” which is just coming into view at the end of the book.

I think in this moment it’s vital that everybody – citizens, artists, human beings – start imagining radically different ways of being. Because instead what’s happening is other people are imagining these things for us – technologists are saying the future will be like this, but what if you don’t want AI everywhere in your house, and your phone to talk to your belt buckle to speak to your shoe? What if you don’t want to be disturbed all the time by technology, what if you don’t want the economy to be a free-for-all where everybody is a self-employed contractor? What if you don’t want your kids to go to a school where they sit behind desks and memorise things all day? It seems we’ve become so full of anxiety about the future that we’ve almost stopped looking for new ways of doing things. We need to look. And so I think this idea of looking forward with a degree of hope is a vital political gesture. If we don’t do it, then we hear all of these counterclaims that seek to take us back to something that perhaps wasn’t that great at all. Maybe it wasn’t a better situation than today. And in any case we can’t get there. We can’t get to the 1950s, we can’t get to the eighth-century caliphate, we can’t get to the Britain of Empire, so it’s important to imagine a different future.

If behind that tree is a lion and you glimpse a little bit of yellow, you should panic: it’ll save you. If you reason that there’s a very low likelihood of it being a lion and just sit there, you’ll get eaten.”

As you say, populist, alt-right politics are usually nostalgic for the past. How and why have those politics come to the fore now, after decades of more enlightened debate?

I think levels of anxiety have gone up disproportionately to the reality of human life on the planet, which is actually better than it’s ever been. People are living longer, their chances of a violent death are going down, the gap between the education of women and men is diminishing, the poorest people are consuming more calories. The overall trend is quite positive, and yet if you ask people where is the world headed, they tend to think it’s headed to hell in a handbasket. I think part of the reason for that is that we are designed biologically to give much more weight to fearful or negative information. You know, if behind that tree is a lion and you glimpse a little bit of yellow, you should panic: it’ll save you. If you reason that there’s a very low likelihood of it being a lion and just sit there, if you’re wrong you’ll get eaten.

That’s a why a writer remembers one bad review and not a hundred good ones, that’s why walking on the street you remember the one racist thing that was said to you in the year ahead of a thousand pleasantries. Given that we are wired in that way, and are bombarded with news information full of terrorism, crime, economic threat, we are fundamentally becoming uncalibrated, we’ve lost our sense of what is actually going on. It seems that things are disastrous, and that’s where the rise of ‘alternative facts’ comes from. Because these negative stories have created a sense of such extreme anxiety, any news or information that doesn’t mirror our sense of anxiety feels false. Why aren’t they reporting on the masses of murders being done by migrants? Because there aren’t that many. So let’s have a daily report of crimes by migrants; there are probably quite a few. What would be more interesting, though, is how do they compare to crimes by locally born people, per capita? You might find that the migrants commit far fewer. But if you just see the number of migrant crimes, and there’s like four rapes today and one murder and 56 assaults, you think, that’s exactly how I thought it was, it’s out of control.

In the same way that after a long time of not having enough calories we now live in a situation that to live healthily we have to control how much we eat and what we eat, I think after a long time of having insufficient information, we now live in an environment where we’re going to need to control how much information we take in, and what kind of information. And that process has only barely begun. It’s as though the Big Mac and the supersized milkshake have just been invented, and the first person to point out that it’s going to give you a heart attack and diabetes hasn’t yet spoken up. But I think we really need to introduce fasting and dieting and mindfulness to the way in which we allow information to approach us, because it’s throwing us off balance.

What was behind your choices of Mykonos, London and Marin Country as locations for teeming refugee camps and emerging townships?

Almost all the places in the novel are places that have been important in my life. I spent part of my childhood in the Bay Area, south of San Francisco. I spent my 30s in London, I’ve been to Mykonos many times, I live in Lahore, which in its physical and cultural setting is not unlike the city that Saeed and Nadia live in, at least at the very beginning of the novel. So the geographic settings of the novel are in a way autobiographical.

I think we really need to introduce fasting and dieting and mindfulness to the way in which we allow information to approach us, because it’s throwing us off balance.”

I think it does help throw the issues into the spotlight for Western readers familiar with those places; for Americans to think about shanty towns going up just over the Golden Gate Bridge, or Londoners to imagine Hyde Park and Kensington filling up with millions of refugees.

The interesting thing is that the migrant invasion of Kensington and Chelsea happened long ago. The world described here where these mansions are full of people born somewhere else is the world we live in, it’s just a different socio-economic group. What you see in the Bay Area is that the city has become very expensive and wealthy, but lots of communities around San Francisco are very poor. Often in America you find these wealthy cores surrounded by impoverished rings. Not just in America, all over the world. And so the shanty towns may not yet exist in Marin, but they do exist in other places.

To what extent did you draw on your own departures and arrivals at key points in your life between San Francisco, Lahore, London and New York?

Very deeply. That experience of what leads someone to leave a place, and what it feels like to be in a new place, what happens to a couple when you move, what happens to an extended family and past generations, all of those feelings are built into this book. The novel is geographically and emotionally autobiographical to quite a considerable extent, even though the narrative has not particularly come out of my life.

You studied creative writing at Princeton with Joyce Carol Oates and Toni Morrison. What were their biggest influences on your writing? And what was the best piece of encouragement or advice you received?

They were both incredible teachers. Being in their presence and having them read my work gave me permission to dream that I actually could be a writer. I entered university not really thinking I could be a novelist, and I left convinced that it might be possible, and that’s a huge gift. Perhaps the biggest thing Toni Morrison taught me was to read my work out loud. She would read our work out in the class, and she’s a beautiful reader; she could read the back of a cornflakes box and you’d think, this is magnificent! She used to read our stories and they sounded fantastic, and I remember thinking I really have to interrogate my work with my ears. Joyce Carol Oates taught me you need to be very unsparing with your work: hold yourself to as high a standard as you can. Initially that seems quite destructive, you become discouraged, but really what it means is you accept the drafting process as natural, and then each time you proceed over it and over it, it can get better. Those are two of the fundamental ways that I still approach writing today.

What have you been working on since you finished Exit West?

I’ve written some essays, but mainly the few months when a book comes out are a write-off. You travel a lot, you give a lot of talks and your head is all over the place. So I’m in my fallow period. It usually lasts a year, sometimes two, when you hand in a book and it’s getting published, and I don’t really try and write a novel in that time. I might write essays and occasional stories.

Is there something lurking in your notebooks that might be the germ of the next project?

I don’t know. I’m intrigued by the idea of writing a children’s book. My daughter’s 7 and she’s asked for one, and I figure I don’t have much time if I’m going to do it, so I’m thinking about that. I’m just going to sort of sit and wait.

Perhaps the idea will come from her…

She actually gets stories on demand most nights. You know, bespoke: “I’d like a story about this,” and then when I’m telling a story she can easily say, “No, no. He doesn’t do this, he does that.” So it’s a kind of interactive storytelling, and she likes the idea of co-writing stories: “Let’s sit down and write a book together.” It could be very interesting. I don’t know if I’ll do it, but I’m thinking about it.

As soon as she was born, you decided to relocate to Lahore. Did that impulse take you by surprise, or is it something you’d always harboured?

I always thought I would go back one day. Maybe not permanently, just for a few years possibly, and after our daughter was born I thought if we don’t go back soon we might not go back. She’ll start school, we might think Pakistan is too unsafe or too unsettled, so if we want to go we should try it now. So she prompted that move in a way, it felt a little bit now or never. But I guess I imagine my kids will live in multiple countries and study in different places, because that’s how I’ve lived. They’re aware of my history and they’ve been to many of my places. They’ve been to London and New York and they know these cities a bit and they keep coming, and they spend time with my friends’ kids and they’re forming their own friendships, and so even though they live in Lahore, they are interested in and feel comfortable with being in other places. Whenever I’m about to travel, my four-year-old son says, “I want to go too!” He loves getting on an airplane and going to a new place, for him it’s an amazing adventure, and so I’d like to keep that feeling.

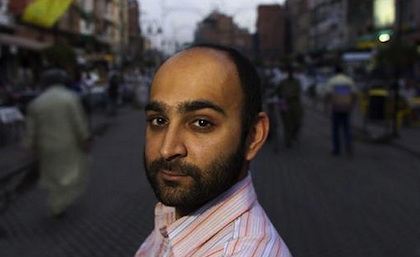

Mohsin Hamid is the author of Moth Smoke, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, and Discontent and its Civilizations. His essays and short stories have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker and elswhere. Exit West is published by Hamish Hamilton in hardback and by Penguin in eBook and audio download.

Mohsin Hamid is the author of Moth Smoke, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, and Discontent and its Civilizations. His essays and short stories have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker and elswhere. Exit West is published by Hamish Hamilton in hardback and by Penguin in eBook and audio download.

Read more

mohsinhamid.com

@mohsin_hamid

Author portrait © Ed Kashi

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista