Ukamaka Olisakwe: Breaking free

by Mark Reynolds

“An unflinching portrait of survival and strength… deeply moving.” Julianna Baggott

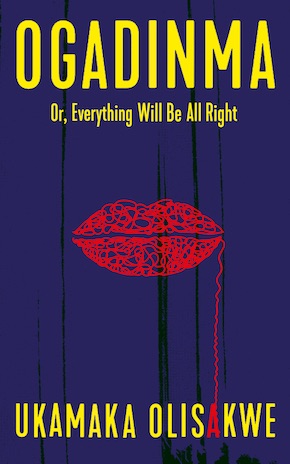

Ukamaka Olisakwe’s fierce, measured, ultimately hopeful novel Ogadinma, rightly dubbed “a feminist classic in the making”, is an unflinching portrait of female survival and inner strength in the face of multiple harrowing obstacles in modern-day Nigeria, where patriarchal rules and behaviours are ingrained but fought against daily by the nation’s women. The eponymous heroine is exiled from her Christian family in Muslim-dominated Kano at the age of 17 after an episode of sexual abuse thwarts her plans to study at university. Housed by relatives in Lagos, she is nudged into a passionate relationship with an older man, which goes sour as the corrupt military regime that backed his enterprises is replaced by another with different allies and followers. But, ever resourceful, Ogadinma picks herself up, determined to escape her seemingly inevitable fate.

MR: Ogadinma’s journey immediately recalls the obstacles, frustrations and predatory sexual behaviour faced by the likes of Flaubert’s Emma Bovary and Hardy’s Tess – but shockingly these events take place as recently as the 1980s. Did you have such classic fiction in mind when you chose to frame her story?

UO: When I wrote Ogadinma, I wasn’t thinking about Emma Bovary or Tess Durbeyfield. My protagonist is, rather, a composite of the women I know, whose experiences are similar to the beloved characters in Flora Nwapa’s groundbreaking novel Efuru and Buchi Emecheta’s seminal work The Joys of Motherhood. Ogadinma is my love letter to these women in my life, whose marriages failed or succeeded, who are my heroes. Ogadinma is my daily reminder that it is okay to put myself and my mental health first, and to always walk away from toxic situations. I wouldn’t have been able to tell this story if I hadn’t lived among these women who pushed back against society’s expectations of how a woman should perform womanhood.

Ogadinma comes of age around the time you were born, and already by the end of the book she is able to begin to make life choices on her own terms. How have prospects and freedoms for women improved in Nigeria since that time, and what are the continuing challenges of toxic patriarchy in the country?

Gender inequality and gender-based violence are some of the challenges we all are battling in our various communities around the world. We have variants of this toxic patriarchy that threatens the very existence of women. I think what I tried to do with Ogadinma was to show that it doesn’t matter if the novel is set in the 80s or the 2000s, these issues still persist. The #MeToo movement pulled the veil off society and exposed the rot that has been eating into our fabrics. This rot, in the form of sexual or physical abuse, is no different from the horrors the likes of Angelina Jolie, Cara Delevigne, Gwyneth Paltrow and over eighty other women said they suffered at the hands of Harvey Weinstein.

I wouldn’t have been able to tell this story if I hadn’t lived among these women who pushed back against society’s expectations of how a woman should perform womanhood.”

Ogadinma is exiled from Kano, where you grew up, to the bewildering megacity of Lagos. How does life in the two cities compare, then and now?

I left Kano in 2001 and never went back, and so I can’t authoritatively speak on how things are in that city today. However, Lagos is now a frustrating phenomenon. I had grown up hearing stories about how Lagos was the New York of Nigeria, and when I visited for the first time in 1999, I discovered that the megacity wasn’t anything like the New York I had seen in the movies or in commercials; this one was better, colourful, and chaotic too – the endless traffic, the crowded streets and the roadside markets, everyone hastening up and down the streets and hopping off and onto the peculiar yellow buses. Lagos, back then, was so startlingly disorienting that I wondered how I survived the conservative and annoyingly religious community I was raised in. Lagos was reckless too, and I thrived in that recklessness. Ha! I began to wear trousers and midriff tops and bodycon dresses and tomato-red lipsticks – things my community in Kano had deemed sinful. The megacity has since lost its flavour, thanks to a new insidious classism that excludes the poor, with successive state governments demolishing shelters in low-income areas, just so to remodel the landscape and fit into the concrete-and-glass images the Western media has sold us as ‘civilisation’.

What role does the church have to play in promoting equality and modernity in Nigeria?

I wonder what you mean when you say “modernity” – but I do know that the Christian faith, which white missionaries brought to Nigeria in the late 1800s and early 1900s, took many communities a hundred steps back in matters regarding gender equality. Before the advent of Christianity, children in my community belonged their mothers, women contributed actively in their communities and served as mediators between the people and their gods. The almighty Igbo god Ani, whom many gods reverence, is female. But then the missionaries came with their Bibles and told the men that God is a man, that women came from men’s ribs and are subordinates, and should not speak in the church; that children belong to their fathers, hence the introduction of the Father’s Name/Surname; that women must submit to their men according to the words of Saint Paul, etc., etc.

I must admit though that the old Igbo religion and cultural practices weren’t perfect, and our women today have used that tool – Christianity – that segregated them to push back against practices like the funeral rites, where the widow is essentially persecuted and punished following her husband’s death. The women in the Anglican Church and Catholic Church, for example, formed associations, worked with their priests, and pulled down some of those old norms.

And in what ways can the international community help to improve conditions in the country?

I think that word “help” has become quite problematic because of the obvious power dynamic it encourages – upholding one party as superior, while reducing the other as impoverished. Also the word “improve” is too Western, in the sense that countries which aren’t geographically situated in certain parts of the globe and which hold fast onto their non-Western ways of being, are considered “third world” and so are perceived to need “saving”. I think, though, what the international community needs to do is to cut down on the brutal economic policies that deplete the gross national income of countries they have dismissed as third world. The white media, also, can help improve the image by quitting their negative portrayal of these countries. The most recent is the shocking obsession with why Africans aren’t dying of Covid-19; the BBC faced a lot of backlash recently after they tweeted a dreadful headline about how poverty could explain the low coronavirus death rate in Africa. That pairing of Africa and poverty is old and tiring and sickening – this same stereotype has been fed to young people in the West who, when they hear the word Africa, immediately conjure up a jungle populated by disease-infested people living in war-torn communities, who need to be saved.

So, if the international community want to really help, they can begin by considering our humanity.

You left your husband and children behind in Nigeria when you were invited onto the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. Did you have any doubts about taking your place on the course, and remaining in the US to pursue your PhD?

I have an agreement with my family. They are very supportive of my pursuits; they are my greatest cheerleaders and always, always remind me to put myself and my mental first. So, yeah, I didn’t have any doubt at all about them supporting my dreams in academia.

There is a very beautiful Igbo proverb that explains how we care for and raise our children: we say, ‘Ofu onye adiro azu nwa,’ which can be translated to mean, ‘One person does not raise a child.’”

Who looks after the daily care of your children, how often are you able to talk with them and visit, and what kinds of negative and positive responses have you received from family and the wider community to your long absences?

My children (17, 16, and 13) have their father, his relatives, my relatives, in fact, our entire community. There is a very beautiful Igbo proverb that explains how we care for and raise our children: we say, “Ofu onye adiro azu nwa,” which can be translated to mean, “One person does not raise a child.” This is because we believe in community. That is not to say that I don’t have relatives who have qualms with my ambitiousness. However, my children are constantly showered with love, and smothered by it, even. The first cultural shock I experienced in the United States was how individualistic the society is, with everyone minding their business, walking off the curb rather share a path with you, winding up their windows when you walk by, hastening down the street when they see you coming; Americans want their space. It took me a while to adjust to this isolatory lifestyle. And I am glad that my children have my family in Nigeria. I miss that community, and I visit every holiday. And despite the distance between us, technology has made it possible for us to keep up with each other’s daily lives.

In what other ways have you struck out for your own independence and broken society’s rules?

I think being an unapologetic feminist is breaking society’s idea of what a woman should be and how she should behave. Writing stories that centre wayward and disruptive women is breaking society’s rules. Moving away from home to pursue a career in the creative industry and in academia is breaking the rules and ordinances guiding the Christian faith. I was raised an Anglican and married into a Catholic family; there are unspoken rules I am supposed to adhere which I do not care about: I am loud. I use the word ‘fuck’ a lot. I do not live with my husband. I am ambitious. I am selfish. I have become everything society doesn’t want her Christian daughters to become.

Indigo sold the Nigerian English-language rights in Ogadinma to Masobe, a forward-thinking young publisher. What makes Masobe a good home for your novel, and how do you expect your book will be received by Nigerian readers?

Masobe Books is an amazing publishing outfit. Founded only two years ago, they have covered so much ground and stirred conversation about literary citizenship in Nigeria. I love their vision, and I think what drew me to them was how they not only strive to fill the stores with books, but also to get the books into school libraries and into communities where such resources are needed. I hope that my Nigerian readers will understand Ogadinmaand why that story was necessary. I hope that the book will add to the conversation about our fight for women’s empowerment and gender equality in my community and around the world.

What is the state of book publishing in Nigeria generally today?

So much is happening at home. We have new publishing firms like Masobe Books, Ouida Books, Griots Lounge, Quramo Publishing, Narrative Landscape and many others. Twenty years ago, we wept about the near-absence of these presses. Today, new ones are springing up and I think it is a good time for the young Nigerian writer, who before now had to look toward the West to be heard.

I deeply, deeply love these writers and can’t stop recommending their works to anyone I meet, because they are brilliant and the stories they are telling are necessary and timely.”

A new generation of Nigerian authors including Chigozie Obioma, Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀, Chibundu Onuzo and Oyinkan Braithwaite have been making a splash internationally in recent years. Why do you think their time has come, and which other Nigerian authors should we be looking out for?

Their time has come – and always should come – because we are Nigerians and Naija no dey carry last. LOL. I deeply, deeply love these writers and can’t stop recommending their works to anyone I meet, because they are brilliant and the stories they are telling are necessary and timely. Other writers you should read include Lesley Nneka Arimah (who is my favourite writer in the whole world today), Suyi Davies Okungbowa, ’Pemi Aguda, Ope Adedeji, Arinze Ifeakandu, Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo, Abi Daré, and so many others.

You wrote an optimistic piece for the New York Times about the 2015 election when the incoming President Buhari promised “a country free of corruption, where people won’t need to uproot their lives to find safety, where our voices are heard, where we aren’t judged by our religion or ethnicity.” He won a second term in 2019. How would you say he has shaped up as leader, in the light of those pledges?

I rarely talk about that piece because I was very optimistic about his presidency, naively so. And what’s particularly interesting is that he served as the military head of state in the 80s, around the time Ogadinma is set, and decades later had rebranded himself as a statesman. He spoke about his dreams for the new Nigeria, and I was sold on that vision. I am shamelessly optimistic. I still look forward to an improved Nigeria. I stay hopeful.

How do you expect the upcoming US election to play out?

I will dance on the streets and scream my lungs out the day Joe Biden is declared the winner of the presidential election. I have problems with Biden’s past politics and his social proclivities. However, this election is bigger than him; it is about what policies get signed into law and what they mean to the low income earners, the Black and brown peoples, even immigrants and international students living in that country. So, yes, I will dance the day a Democrat is declared the winner of the election.

You wrote the screenplay for the Nigerian TV series The Calabash. Do you have hopes for a TV or film adaptation of Ogadinma?

That wouldn’t hurt, would it?

Are you still working as a journalist, or are you now devoting your time to fiction?

I am partially devoting my time to fiction, while also pursuing a PhD in English and teaching English Composition to freshmen.

What are you writing next?

A collection of short stories. A fantasy novel. A memoir.

Ukamaka Olisakwe is a Nigerian novelist, short story writer and screenwriter. In 2014 she was chosen as one of sub-Saharan Africa’s most promising writers under the age of 40. She was born in Kano, and in 2016, was a resident at the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. Her writing has appeared in Catapult, the New York Times and The Rumpus. She wrote the screenplay for The Calabash, a Nigerian television series that premiered in 2015 on Africa Magic Showcase. Ogadimna is published by The Indigo Press.

Ukamaka Olisakwe is a Nigerian novelist, short story writer and screenwriter. In 2014 she was chosen as one of sub-Saharan Africa’s most promising writers under the age of 40. She was born in Kano, and in 2016, was a resident at the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. Her writing has appeared in Catapult, the New York Times and The Rumpus. She wrote the screenplay for The Calabash, a Nigerian television series that premiered in 2015 on Africa Magic Showcase. Ogadimna is published by The Indigo Press.

Read more

@MsOlisakwe

@PressIndigoThe

Author portrait © Elizabeth Reiss

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark