The end of the world that never came

by Mika Provata-Carlone

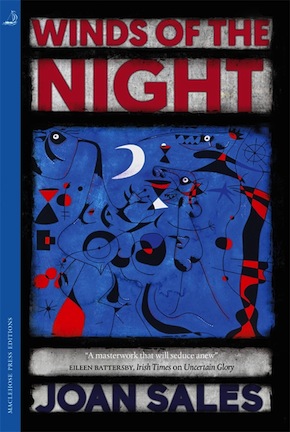

“A major novel that expresses the disillusion of a generation.” Literary Review

Some books speak infallibly and for eternity; no matter their narrative temporality, the very magnitude of their resonance transcends their present, encompasses the past, often pre-empts and preconditions the future on a universal scale that gives them a sense of almost divine omniscience and awesomeness. These will eventually become what we call rather inadequately the Classics – for it is often the most subversive and rebellious, un-classical literary gestures that are endowed with that particular kind of purest majesty.

Other books conversely are like lightning bolts in the darkness of a storm. They tremble in their every fibre and sinew with the urgency, tragedy, glorious euphoria or the volatile, uncapturable and transient spirit of a single era, dark or light, ponderous or frivolous, critical or inconsequential. They will produce a momentous, blazing flash, a shattering quake, and then disappear, perhaps to be retrieved and rekindled, so that their echoes may be sounded yet again.

Winds of the Night belongs to that second category. It is a story about the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War, a very personal, idiosyncratic narrative that claims for itself the value of an absolute chronicle of the chaos, violence, vacuity, loss, despair and revelation that was Catalonia during the time of fighting and also under Franco’s pitch-dark years, if not well beyond. It is a novel as much as it is a testament, a land-survey map of the state of a nation’s psyche and of the fate of individual souls.

This grand tableau d’histoire is a Brueghel the Elder canvas of the darkest and most nightmarishly fantastical riddles and details. The writing is obsessive, with overarching, compulsive use of allegorical images and metaphors, an almost possessed sense of atmosphere and spatial associations. It is claustrophobic, ruthless in its evocation of a fatality of doom, morbidity, a hallucinatory reality and consciousness, of tragedy, hope, and a yearning, pleading humanity. It is an endless voyage au bout de la nuit where humanity has become an anti-human state of narcosis. Those who have read Sales’ Uncertain Glory will seek a light, a conclusion, that perhaps is not – cannot be – there; those who read Winds of the Night as the autonomous volume it has posthumously become will long for a frame of reference, for a grid that solves the coded enigma. Sales provides everything and nothing of the above in this second part of his Catalonian epic of dystopia but also of a certain revelation. His flashback narrative, where the future and the present merge and dissolve into one another, these abortive children of a barren, troubled past, revolves around one central query: is a vision of the truth possible for mankind? Is our perspective limited, biased, circumscribed by external factors, or are we responsible – historically, privately and absolutely – for our “blindness and insight”?

Sales’ novel is the flip side of Guernica: the impossibly, shamelessly parcelled memory and conscience of those who filtered everything through the prism of power, interest, ambition, desire.”

Using crisp, pithy sentences, sharp, unwavering observations, but also astonishing statements ranging from the macabre to the bemusing, Sales plays with our own perception as readers, and with our capacity to derive meaning, to sustain the connection with voices and lives beyond sense and reason. Winds of the Night is an encounter with characters presenting their personal, skewed, self-absorbed memories of the Civil War. Their every utterance undermines evidential factuality, while reinforcing a brutally solid reality of violence, terror, petty interests, dark ambition. Like post-Holocaust writers, Sales’ ultimate aporia is whether memory or its writing can exist after the end of history – that history. “Only those who forget rise to the top,” we are told with supreme irony: history is a meander, a deadly, morbid labyrinth from which no one can escape, for which there is no Ariadne’s thread, except perhaps the writing of fiction – the web of words and plots that will push aside the cobwebs of multiple falsehoods as well as truths.

Sales’ novel is the flip side of Guernica: rather than the mangled, horrifically dismembered bodies and hearts of the victims, here are portrayed the impossibly, shamelessly parcelled memory and conscience of those who filtered everything through the prism of power, interest, ambition, desire, on either side “a mishmash of murky insights, lunatic insinuations, and incredible half-truths.” It is often like an Otto Dix painting of distorted close-ups and dizzying panoramic shots, of infernal sharpness and darkness, carnality and howls of spiritual despair.

What does it feel to remember horror and numbness? Culpability, complicity, the warping of motives, facts, aims and circumstances? Or even inaction, willing or unwitting neutrality, or the shying away from committing one’s life to a place in the grand scheme of things? To the world stage rather than the wings? Sales probes, with scalpel-like incisions, into social constructs, into myths of cultural, historical or ideological identity, the process of fabrication and the ideal of authenticity; he exposes minutely and with almost self-indulgent lengthiness the practice of appropriation, dispossession, cultural colonialism, racism, the genocide of souls and human beings. Catalan vs. Spanish, low vs. high, propaganda, history, myth and reality, are scrutinised time and time again, always under the prism of blindness and insight.

“It is the perfect distillation of those cries of anger, falsehood and despair that clashed at that particular, tremendous and tragic moment in time.”

“Perhaps people, like nature, are indifferent to catastrophes; perhaps that is how it has to be; nature is indifferent and couldn’t care less so it can build afresh after every flood and earthquake; perhaps the masses have to be frivolous, so the world can survive in eras like ours.” What place has mankind reserved for empathy? What constitutes survival? Is humanity animal, plant or mineral? Spirit? And what would that be? “The only consolation left to me thirty years later, with my life wasted, is that I am a loser among the winners.”

Winds of the Night is not a satisfying read; yet it is the perfect distillation of those cries of anger, falsehood and despair that clashed at that particular, tremendous and tragic moment in time. It is a katabasis into the darkest depths of the human soul and of history as much as it is an array of unreliable flotsam and jetsam of memory. The newsreel-like images of Spain devastated, festering, or benightedly proceeding with the gestures of life are so blurred and sharp at the same time as to be agonisingly shocking, Buñuel-like, but without a trace of surrealist veneer. Truth and hallucination, existentialist relentlessness, are here stark and inexorable.

Joan Sales describes Cruells, the main character of Winds of the Night, as “a lost neurotic, feeling his way in the dark, while the wind of schizophrenia blows dust in his face. It is the story of a sick mind. A mind made ill because of the immense scandal of National-Catholicism.” One could also add that it is a mind seeking the light of humanity beyond the most extreme test of endurance, a conscience yearning for a night of conversion, a day of reversal, a way of return – Sales, after all, translated Kazantzakis and Dostoyevsky, as well as François Mauriac; Bernanos is one of the voices he emulates, and Mexico the world of life and death that perhaps inhabits and feeds his imagination. Winds of the Night will leave you with the bitterness and acrid unsettledness of the blackest Goya sketch from his so-called mad period. It is a homage to loss, a testament of pain, an audacious literary claim. Peter Bush’s rather argotic translation sometimes buckles under the weight of Sales’ ingenious density, the impossible couplings of meditative elegiac prose and repulsive egomaniac fabrications that interlace in the coalescing exchanges of his characters. Yet this unyielding edifice of words, this crumbling narrative of a life – of many lives – will not fail to arrest you, grip you, shock you, awaken you to its urgency and ultimate plea of humanity.

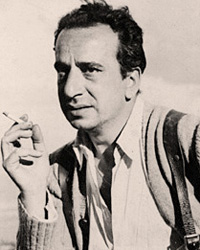

Joan Sales (1912–1983) was a Catalan writer, translator and publisher. He obtained a Law degree in 1932 and was a member of regional anarchist and communist groups. In the Civil War he fought on the Madrid and Aragonese fronts before going into exile in France in 1939. He moved to Mexico in 1942, returning to Catalonia in 1948, after which he began working as a publisher. Uncertain Glory, his crucial testament, was first published in 1956, though a combination of censorship and Sales’ tendency towards revision meant that a definitive edition was not available until many years later. Winds of the Night, translated by Peter Bush, is published by MacLehose Press.

Joan Sales (1912–1983) was a Catalan writer, translator and publisher. He obtained a Law degree in 1932 and was a member of regional anarchist and communist groups. In the Civil War he fought on the Madrid and Aragonese fronts before going into exile in France in 1939. He moved to Mexico in 1942, returning to Catalonia in 1948, after which he began working as a publisher. Uncertain Glory, his crucial testament, was first published in 1956, though a combination of censorship and Sales’ tendency towards revision meant that a definitive edition was not available until many years later. Winds of the Night, translated by Peter Bush, is published by MacLehose Press.

Read more

Peter Bush is an award-winning literary translator who was born in Spalding, Lincolnshire, and now lives in Barcelona. His translations from Spanish, Catalan, French and Portuguese, include works by Josep Pla, Merce Rodoreda, Fernando de Rojas and Jorge Carrión.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.