Chibundu Onuzo: Ancestry and identity

by Mark ReynoldsChibundu Onuzo’s latest novel Sankofa is an entertaining and eye-opening story of a woman in search of her roots. Anna Bain is a mixed-race woman of 48 who grew up in London with her Welsh mother Bronwen, knowing little about her African father who in turn has no idea of her existence. After her mother dies, Anna opens a trunk of her belongings which contains the diary of Francis Aggrey, a West African student who lodged with Anna’s mother’s family in London in the 1970s. In it, he outlines a brief fling with Anna’s aunt Caryl, before he enters into a deeper affair with 18-year-old Bronwen.

It’s been thirty years since Anna gave up asking her mother for information about her father, and here she suddenly has access to his thoughts and preoccupations at exactly the time he was wooing her. Digging deeper, she discovers that Francis changed his name to Kofi Adjei, became a freedom fighter and was jailed on terrorism charges. Then on his release he became a populist political leader and won a landslide victory in his country’s first democratic election as the Diamond Coast was reconstituted as newly independent Bamana. He became Prime Minister, then President, and in the eyes of many a ruthless dictator surrounded by obscene wealth and privilege. And he is still alive.

Against the wishes of her grown-up daughter Rose, Anna cuts short divorce proceedings from her estranged husband Robert and flies out to the Bamanaian capital Segu to find her father. Mixing together real and imagined places, histories, folklore and customs from across the continent, Anna’s journey to her ancestral homeland becomes a tender, absorbing and frequently funny exploration of identity and the post-colonial experience as viewed from all sides.

Mark: In the acknowledgements you thank journalist Joseph Harker for telling you his story. Which elements of his story did you borrow from, and how did you go about making them your own?

Chibundu: I wouldn’t say I borrowed directly from his story, but his father came over as a student to England and returned to Nigeria, and he didn’t meet him until he was an adult in his twenties. So that was part of what formed part of the kernel for the idea, but from there Anna’s journey to meeting her father is very different.

Maryse Condé’s Segu was also a clear influence. How do her Segu and yours differ?

Maryse Condé’s book is a multigenerational saga as she follows a family from pre-colonial times all the way up to the early twentieth century, whereas mine is much more tightly told, I’m only looking at Anna and her father. But I love what she did with Segu, and how she created a world for you to inhabit. Her Segu is a historical place that you see over a century how it changes, whereas my Segu is more of an imagined backdrop to Anna’s journey.

There was a lot of idealism, a lot of big promises made, and not all but quite a few of the leaders went on to squander that hope with the decisions they subsequently made.”

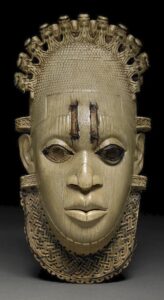

Queen Idia carved ivory mask-shaped pendant, inlaid with iron and bronze, 16th century © The Trustees of the British Museum

In fact your Segu and the tiny enclave of Bamana could represent any African nation from Mali to South Africa. So did you set out to write about a pan-African experience of colonial rule and its aftermath?

Yes, a hundred per cent. That’s the point I was trying to make, and that’s why I chose a fictional country. A lot of African countries have this in common, that independence movement. There was a lot of idealism, a lot of big promises made, and not all but quite a few of the leaders went on to squander that hope with the decisions they subsequently made. I’m not the first author to reflect on this. Chinua Achebe does it really well in A Man of the People, and then also The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born by Ayi Kwei Armah, they both look at that colonial and immediate post-colonial moment, and where it went wrong.

And in the same way Francis, or Kofi, could stand for many misunderstood, distinguished but self-interested African rulers. Is he modelled on any in particular?

No, he’s definitely not modelled on one in particular, I draw from different stories. But I am interested in that generation, and I did my research on a group called the West African Students’ Union, which was formed in 1925 and was active into the late 1960s. Some of its members went on to be leaders, for example Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, and when they were students this sort of big, idealistic talk started from there. So I drew heavily on that research in creating Francis’ character and his experiences in London as a student.

The racism that Francis encountered as a student in 1970s London certainly fuelled his political outlook.

Most of WASU’s members had accounts of racism, from the more subtle to the more in-your-face, deliberate, and it’s something that historians have commented on, about how many African independence leaders got a stronger sense of their national identity, or their African identity or their black identity, when they moved to London and experienced that racism. Nkrumah talks about it in his autobiographies, another Ghanaian man called Joe Appiah talks about it in his autobiography, as well as Ras Makonnen from Guyana. It was part of the experience, it was almost like a rite of passage, and some of them were quite shocked by the level of racism they experienced. Depending on what colony they came from, not many of them would have had day-to-day experiences with white people. So if you were living in a colony that had in your area maybe one white district officer to ten thousand Africans, for example, then you probably didn’t have much social contact with white people. So to come to England was very difficult. They couldn’t find accommodation – Wole Soyinka writes about this in his famous poem ‘Telephone Conversation’ – accommodation was a really big issue, and sometimes they’d be refused service at restaurants. All those sorts of experiences definitely made them band together more, it made them seek out the company of other black people, other Kenyans, other Nigerians, Caribbeans. And then by seeking out their company, they began to have all these political discussions and debates.

The myth of the Sankofa bird depicted on the book’s cover teaches that we must go back to our roots in order to move forward. How is does that myth play out in Anna’s story?

That’s what she’s doing: she’s going to find her father, and she’s doing it at an age – she’s in her late forties – that people around her don’t fully understand. She has a conversation with Blessing, the wife of one of Francis’ former student friends, about going to Bamana to find her father, and Blessing is confused, she’s like, “You’re a fully-formed adult. Why are you going to look for this man, at this age?” But I think that’s what the idea of Sankofa encapsulates: how do you move forward if you don’t engage with your past? And I think it’s an idea that can be transplanted to any community. In England, in Britain, in America, wherever, you have to face even the things in your past that are not so pleasant. In the UK, for example, with slavery and the legacy of slavery, there definitely needs to be a Sankofa moment where we have to look back and move forward, we have to do both.

I guess that’s just the way history is. Everybody’s looking at the same thing, but depending on what they are bringing to it, their understanding of it, their perspective of it is very different.”

What roots do you think Rose might need to return to? She comes across as restless but fixed in the present.

Rose doesn’t have a lot of page time, but she is definitely a character that interests me. I’ve never, ever considered writing a sequel to the book, but if I ever did it would be because of Rose. Because yes, you’re right, she’s sort of restless and maybe she might also benefit from a trip to Bamana, but it would be interesting to see how that would play out for her, what conclusions she would come to from her trip.

Kofi’s country home Gbadolite is modelled on Mobutu’s ‘Versailles of the Jungle’. Have you been? I don’t suppose any people have.

No, I haven’t been, but I looked at pictures, I looked at photographs and videos, and it was really interesting that space, especially seeing it now, because it lies mostly in ruins. I picked things from different countries and different places because of the point that you made, that it could be the story of any post-colonial African state. We’ve seen these leaders that came, squandered resources, took resources and used them for their personal gain and so on and so forth, we’ve seen this story in many different countries.

Anna visits a slave fort, which is a weird but perhaps necessary kind of tourist attraction. What’s your take on them?

I don’t have a personal take on it, I feel some people go and it’s useful. What I was just trying to capture was the different perspectives on the experience. So the indigenous West Africans who go there as tourists, they go without any heaviness, it’s almost like a day at the beach, while for the African-Americans, the Africans in diaspora who are coming back, it’s a much heavier experience, and Anna is sort of in the middle of this. Her ancestry is not of former slaves, but then at the same time she’s not quite among the West Africans that she sees taking selfies, laughing and running on the beach while some people are crying. And I guess that’s just the way history is. Everybody’s looking at the same thing, but depending on what they are bringing to it, their understanding of it, their perspective of it is very different.

It’s an interesting twist in a way that the West Africans are more flippant about it when you might somehow expect the visiting Americans to be less respectful – but these are people who’ve traced their DNA back to the slave trade, so they do have a more serious and engaged view of things.

Yes, I watched videos of people returning, especially to Elmina Castle in Ghana, and it is a very emotional experience, people cry, people sing, again similar to what is described in the book. It’s a bit like the Holocaust memorials and the solemnity that surrounds them, except that the indigenous Africans don’t take it as a solemn situation at all – so there’s a little bit of comedy in there as well.

What are your feelings when you visit the Africa galleries at the British Museum?

Well, the Benin Bronzes in particular have such an outsized presence in Nigeria’s sense of self, for example in the FestAc 1977 festival of arts and culture, the Queen Idia pendant was the logo for the entire festival, and they are so iconic in a Nigerian context, but then to come to the British Museum and just see them in the basement, they’re not even given pride of place, it’s doubly disrespectful. I mean it’s one thing to loot the artefacts, and it’s another thing to put them in the basement! I remember when I first went to see them, especially the Queen Idia pendant, I couldn’t believe that it was the real one, because I just thought this should have pride of place, this is one of Nigeria’s heirlooms, crown jewels, however you want to describe it, and it was just in the basement, and it wasn’t even in a case on its own, it was with like six other artefacts all squashed in one glass case. For me it’s the same as how when you go to the Louvre, the Mona Lisa has its dedicated space, people go there on pilgrimage to see its corner. It’s quite a large room, but it has its own space, and you would think that something like the Queen Idia pendant would be treated with the same respect, but it’s not.

You’ve released a single to mark publication. Tell me about ‘Good Soil’ – and the people involved in the music video.

It was a friend’s idea, who said, why don’t you release a song with your book? I sing, I play the piano, it’s a passion, it’s an interest, it’s something I’ve always done. I sing in my church sometimes, and I play the piano as well, and I thought I’d never have enough time to do it with the book coming out, but then we had a global pandemic and I found I had more than enough time. So I wrote the song first, and recorded it, and then decided to call up everybody I knew to ask if they would be in my music video. I was reflecting on themes of ancestry, identity, being proud of where you’re from, your legacy – all that sort of stuff – and so I called up everybody I knew and asked if they’d like to be in the video. I wanted to have a broad spectrum of black people doing great and amazing things, so there are some more famous people: Christine Ohuruogu, the Olympian is in it, Inua Ellams who’s a playwright, the publisher, writer and broadcaster Margaret Busby. But there are also friends who are doing important work who are not necessarily famous, people who’ve been on the frontline during the pandemic, friends who are lawyers, friends who are architects, just to show a wide range. And I thought it would be a fun thing to do. I’ve never heard of a book soundtrack, so I wanted to make one.

So what are your next ambitions musically?

Now I’ve done one single you sort of get the buzz and I want to do another one. I don’t have an album, an album is a daunting prospect. But another single? Yes, I think I could do that. I performed with friends at the Southbank in 2018, and again in 2019 and then there was the pandemic. I enjoyed it a lot, and it set me off on this journey to the single. So maybe when audiences come back… It’s difficult to plan for live performances the way things are at the moment, but hopefully we’ll be back at some point.

And what are you writing next?

A mix of things. I’m trying to write for television, so that’s ongoing. I co-wrote a short film and that had some success, so I thought, hmm, this is a new avenue to explore. So I guess watch this space. I haven’t decided what my next book project will be, which is quite rare, usually I know what I’m working on next. I’ve started a few things, and nothing has quite clicked into place yet, so early days.

Interesting to hear you’re writing for TV. I wanted to ask if there’s been film or TV interest in this or your other novels. I’d love to see Sankofa and Welcome to Lagos make it to the screen.

There’s definitely been interest, but you know the way things are done in television. I have had meetings but so far nothing has been signed – but hopefully soon somebody will bite conclusively.

Would you consider adapting your books yourself?

Yes, definitely. Sankofa would be a good one to start with, because the story is linear, you’re following Anna on a journey to find her father, so I feel like the steps are clear. Welcome to Lagos has so many different characters that I don’t know how… maybe not a film, but it could be a TV series.

Finally, when we last spoke we discussed how you once said you’d run for public office by the time you were 30. Is it time to put that idea to bed, or is it still an ambition?

Well I’m 30 now, and I definitely have not run for public office, I can tell you that exclusive for free! I guess sometimes you have things that are dreams, and you have things that are plans, so definitely I would say wanting to write for TV is a plan-slash-dream, whereas wanting to run for political office is firmly a dream. So I don’t know, sometimes dreams come true, but we’ll see. It’s definitely not moved to the planning stage.

Chibundu Onuzo was born in Lagos, Nigeria and lives in London. Her first novel, The Spider King’s Daughter, was published by Faber in 2012 and was the winner of a Betty Trask Award, shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize and the Commonwealth Book Prize, and longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize. Her second novel, Welcome to Lagos, was published by Faber in 2017 and shortlisted for the RSL Encore Award. In 2018, she was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, as part of its 40 Under 40 initiative. In 2020 Dolapo is Fine, a short film Chibundu co-wrote and co-produced, won the American Black Film Festival’s HBO Short Film Award. She contributes regularly to the Guardian, has done a talk for Tedx, and her autobiographical show 1991, featuring narrative, music, song and dance, premiered in a sell-out show at Southbank Centre’s London Literature Festival in 2018. Sankofa is published by Virago in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Chibundu Onuzo was born in Lagos, Nigeria and lives in London. Her first novel, The Spider King’s Daughter, was published by Faber in 2012 and was the winner of a Betty Trask Award, shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize and the Commonwealth Book Prize, and longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize. Her second novel, Welcome to Lagos, was published by Faber in 2017 and shortlisted for the RSL Encore Award. In 2018, she was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, as part of its 40 Under 40 initiative. In 2020 Dolapo is Fine, a short film Chibundu co-wrote and co-produced, won the American Black Film Festival’s HBO Short Film Award. She contributes regularly to the Guardian, has done a talk for Tedx, and her autobiographical show 1991, featuring narrative, music, song and dance, premiered in a sell-out show at Southbank Centre’s London Literature Festival in 2018. Sankofa is published by Virago in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

chibundu.onuzo

@chibunduonuzo

@ViragoBooks

Author portrait © Blayke Images

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark

Read our 2017 interview with Chibundu about Welcome to Lagos