Murder, mystery and mind games

by Nathan Oates

The time when writers regarded television sceptically – either as a threat to the storytelling dominance of novels or even, in some cases, as a form of lowbrow entertainment – seems far away now. It’s hard to believe that as recently as David Foster Wallace, writers were expressing anxiety about the relationship between fiction and television, when that relationship now seems so natural and mutually beneficial. Surely this has something to do with what has been called the golden age of television. I’m no expert in the field of TV criticism, but the first big marker in this new age seems to be The Sopranos, a show that fused the violent tensions of a crime story about a brutal mafia family with domestic travails, and even a good deal of humour – I chuckle every time I remember that Christopher, the nephew and right-hand man of Tony the mafia boss, aspired for several seasons to be a writer.

The genius of The Sopranos made it clear to most that TV could tell complex, character-driven stories, of the type some had thought only novels were capable. From there, the relationship between novelists and television blossomed. The number of recent novels that have been adapted into excellent TV shows would be a long list, as would the list of wonderful fiction writers who’ve worked on television shows, from Alissa Nutting to Gary Shteyngart, Patrick Somerville, Emily St. John Mandel and many others.

So, for the sake of this article, I’ll restrain myself to crime and thriller novels that have been adapted to television. There is another, more personal reason for my narrowing of the aperture: my debut thriller, A Flaw in the Design, has been optioned by a film company and so thoughts of how it might find new life as a television series are, hopefully understandably, hard to resist. Most, if surely not all contemporary writers dream of their work making it through the mysterious and opaque maze of options and development and onto the screen.

—

Defending Jacob by William Landay (Apple TV+)

This show, starring Chris Evans as a DA whose son is accused of murdering a classmate, shares many of the same concerns as my own novel: possibly evil children, the wilful and sometimes desperate blindness of parents to their children’s flaws and, more superficially, a lethal car accident. William Landay’s novel is rich with the intricacies of the courtroom and the law, a fact that is brilliantly transposed to the television show with its layers of narrative and telling. There is a frame narrative in both the book and the show that reveals itself in a surprising late turn (no spoilers). This is an example of an adaptation that hews closely to the book, and makes it work wonderfully. The pacing in both the show and the book is a steadily rising boil as the tension and the clues pile up. The ending of the show provides a twist on the book that leaves open the possibility of a second season in a way that the novel precludes, and in fact I prefer the show’s ending because of its heightened ambiguity.

The Outsider by Stephen King (HBO/Sky Atlantic)

This riveting blend of detective mystery and supernatural horror is already perfectly set up for a sequel: Stephen King has already written it as a novella, If It Bleeds. But the HBO adaptation of The Outsider stays close to the narrative of King’s novel of the same name and builds, just as King manages to in so much of his fiction, an inexorable drift of dread so that by the end the suspense is almost unbearable. From Edgar Allen Poe’s first detective stories onward, there has been a hint of the supernatural in crime fiction – the eerie mind of the detective who is surely closer to a criminal than most – and King’s narrative builds on this anxiety to great effect.

Mindhunter by John E. Douglas and Mark Olshaker (Netflix)

Based on a non-fiction book about the creation of an FBI task force to study serial killers, this show demonstrates how exposition and paperwork can be both terrifying and riveting. The serial killers the FBI agent interviews throughout are all imprisoned, and yet their menace, and the menace latent in the agent’s (and our!) prurient interest in the methodical, ritualistic, deranged logic of the killers seeps through, so that we feel we’ve touched evil. That sense of evil staining the everyday is captured by the show’s faintly sepia tones, and its precise use of period details – suits, cars, houses – to build a sense of menace that is embedded in American life.

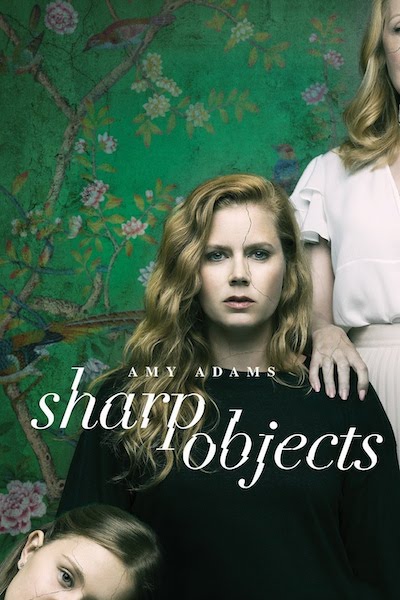

Sharp Objects by Gillian Flynn (HBO/Sky Atlantic)

Amy Adams plays the troubled journalist who is sent from Chicago to the small Kentucky town where she grew up to report on the murder of a child. To say her childhood was unhappy is to put it mildly. As in the book, the viewer of the show sees the impact of her trauma – mostly here in the form of self-harm by cutting – before it is explained, complicating our relationship to the character, and helping fuel the mystery at the heart of the story: who is the real monster? The answer is shocking and upsetting, and even when some of the evil characters are taken away by the police, there is little sense that balance, much less goodness, has been restored. Filmed with an often dream-like cutting and haziness that evokes memory, nostalgia and fear, the show immerses the viewer into the experience of the character in a way normally reserved for fiction, and certain images of violence stick in the mind.

Watching the riveting adaptation of My Brilliant Friend, it seemed clearer to me that this was a story, and indeed an entire world, built on crime and violence.”

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante (HBO/Sky Atlantic)

When I read the first novel in Ferrante’s quartet, I didn’t think of it as a crime novel, but as a story of friendship, and an artist’s coming-of-age story, but watching the riveting adaptation, it seemed clearer to me that this was a story, and indeed an entire world, built on crime and violence. Like the wonderful books on which they are closely based, this show spans decades, and so has several time-jumps and changes of actors, but this causes no jarring at all in the story. Even the children who act in the first season are utterly brilliant.

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty (HBO/Sky Atlantic)

This hugely bestselling novel by the Australian novelist was moved in its adaptation to Monterey, California and is set, like many crime shows, amongst the nefarious doings of the very rich. There’s an impressive ensemble cast, but at the centre is the couple played by Nicole Kidman and Aleksander Skarsgård. On the surface they are almost unbearably beautiful, but Skarsgård’s character is in fact a violent monster who abuses and nearly kills his wife repeatedly. The scenes of domestic abuse are harrowing and hard to watch, and set up the maybe-redemptive crime at the end with real urgency. This show is one of many examples in which the second season carries on well beyond the premise of the book from which it was adapted, bringing in Meryl Streep as Skarsgård’s almost equally menacing mother.

The Undoing by Jean Hanff Korelitz (HBO/Sky Atlantic)

Another show set among the crimes of the super-rich, this time the elites of the Upper East Side of New York City, and again Nicole Kidman is at the heart of this mystery that centres on who is to blame when the mother of a scholarship student at a private school is found murdered in her Harlem studio. A weathered-but-still-charismatic Hugh Grant plays the accused husband, who goes on the run after the murder. Each episode provides an elegant misdirection, so that I felt confident I knew who was truly guilty, while always second-guessing myself. In the end the story interrogates our own inherent biases – cleverly using celebrity in the show, and wealth in the novel – to build suspense and tension.

The Leftovers by Tom Perrotta (HBO/Sky Atlantic)

The mystery underlying this story is an apparent rapture-like experience in which a small portion – two percent – of the population simply disappears one afternoon, and a series of crimes follow in an inexorably escalating manner. The show is about grief and about the extreme fragility of the social contract. Everything here – government, community, family, even the bond between a parent and their child – is shown to be tenuous and thinner than we would hope. The show is a perfect example of using a novel to build out from, over several seasons, an increasingly complex and troubling narrative.

The suggestion of a deep malevolence underlying an apparently peaceful town is offset by the charming cast of characters, especially in the immaculate acting of Alfred Molina.”

Three Pines by Louise Penny (Amazon Prime Video)

Based on Penny’s charming novels, this adaptation does something interesting in that it combines multiple novels into a single season so that, in season one, there is a narrative arc completed every two episodes or so, while a longer thread of mystery runs through the entire season. In this way the show recalls some of the serial mystery narratives of an older television generation, like Murder She Wrote. If one stopped too long to think, in that instance, how a small town in Maine could be filled with so many criminals, it got quite disturbing, and the same is true of the small Quebec town of Three Pines where this show is set. And yet the suggestion of a deep malevolence underlying an apparently peaceful town is offset by the charming cast of characters, especially in the immaculate acting of Alfred Molina who plays the detective at the centre of all the mysteries, Chief Inspector Armand Gamache. He is about as far from the grizzled, drunken detective of hardboiled noir as possible – a gentle, considerate man with a dazzling array of lovely coats, who cherishes family and love and uses kindness as a tool for solving crimes.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (Hulu/Channel 4)

This ambitious adaptation of Atwood’s classic novel is set in a near-future America in which an infertility crisis facilitates the rise of a violent, theocratic government that takes a deranged pleasure in the enslavement of women. Like The Sopranos, this is a genre narrative that transcends easy description. Most obviously it’s dystopian, but the flood of crimes against women makes it a crime novel and a thriller and, increasingly as the show progresses through the seasons, a work of psychological suspense as we watch Elisabeth Moss come unhinged and turn to violence and revenge following years of traumatic abuse. The five seasons of the show range far beyond the source material, and since the first season Atwood has written a sequel of her own, The Testaments, a clear example of the cross-pollination between novels and television.

—

Nathan Oates’ debut collection of short stories The Empty House won the 2012 Spokane Prize. He is an associate professor at Seton Hall University, where he teaches creative writing. He lives in Brooklyn, New York with his family. A Flaw in the Design, his debut novel, is published by Serpent’s Tail in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

nathanoates.net

@NathanMOates

@serpentstail

Author photo by Amy Day Wilkinson