Tishani Doshi: Saying it out loud

by Mark Reynolds

“I want to give this book to the people I love, and say to them, memorise this, never forget.” Jeet Thayil

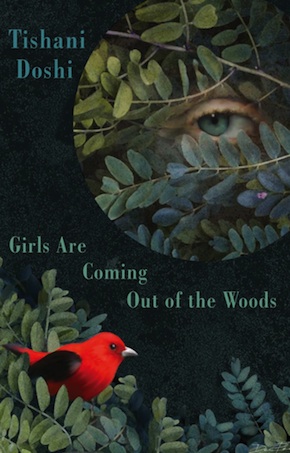

Tishani Doshi’s Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods is an unflinching, tender, witty and wise collection of poems about danger, memory, beauty, time and tide, and transient but treasured joy. I catch up with her at the start of a marathon book tour that takes her from London and Newcastle to Ireland and Cornwall and many points in between.

MR: The title poem was written in response to the notorious 2012 gang rape of Jyoti Singh on a bus in Delhi, and is now dedicated to your friend Monika Ghurde, who was raped and killed in her home in 2016. It is bleak in its frankness and filled with anger, but also affirms that women are rising in ever greater numbers to speak out against sexual assault. How did the poem first form itself in your mind?

TD: The image of the girls marching out of the woods came to me on a bus in Ireland when we were passing some forests. It’s a continuation of an older poem called ‘River of Girls’, where again there’s this subterranean emergence of a very warrior-like female form. Part of the thing for me as a poet is how to write about these things that are affecting us, but in a way that’s not perpetuating it. It’s very difficult to write about violence, and I wanted to have some sense of recognition in the poem. When I started to write it I realised it was coming out as a kind of a chant, like a battle cry, like an anthem. It had that repetition: the girls are coming, the girls are coming. I wrote it because of this one incident, but it was really speaking to centuries of violence and silencing, and so the poem is a way to say that those voices won’t be silenced, and that we will remember. I dedicated it to my friend because it was the first time something like that, that circle of violence, had come so close. And I think it’s inevitable, because of the scale of the violence, that at some point everyone will lose someone they love.

We are a patriarchal society, but if you go back in our history we have always worshipped the mother figure. So that disconnect is something that concerns me, and I think, how did that happen here?”

What do you suppose is at the root of so many brutal attacks in India, and what needs to happen to make it stop?

I’m not sure what can be done to make it stop, except a huge rehaul in thinking. We are a country that has a very strong history of worshipping the female, we have various goddesses and mother shrines, and the idea of feminine power is very strong. We are a patriarchal society, but if you go back in our history you will see that we have always worshipped the mother figure. So that disconnect is something that concerns me, and I think, how did that happen here?

It’s difficult to evaluate the rate of such crimes in any country, because they’re so under-reported.

Yes, and I don’t know that if you looked at the numbers whether India is extraordinarily high compared to other places…

I suspect it isn’t, but there are so many horrific cases that it’s always in the news.

It is, and the positive thing is that the Indian media has made it the news. What’s happened since Jyoti Singh has been a really dedicated move in terms of how we talk about this violence, from not ever talking about it to it becoming very mainstream, very in the streets, very on the front page. And that’s a good thing, because it’s at least saying let’s talk about this. In other countries like South Africa for instance, where again there are a lot of cases, I don’t know whether that kind of discussion is happening. But definitely on news channels and in forums of every kind, people are asking questions about sexuality: what does it mean to be female, what does it mean to be male, what is the crisis, why is this happening, and what can we do to stop it? It comes from educating more children at a very early age about gender divides, not to have this separation. But it’s a huge question.

And yet on the flipside of that, the poem ‘Everyone Loves a Dead Girl’ addresses the prurience of the media.

Yes, that was written after my friend was murdered and I was so shocked that somebody I knew had been portrayed in a way that had nothing to do with her. The media has such a sway and such a responsibility and such a huge power and then that becomes her story, she was forever pinned to being that dead girl found in the bed. And because she was beautiful, because she was young, because of the circumstances of how she was found, it was all really horrible. That’s the ugly aspect, the flip aspect of the media, because you have this sort of reporting without much checking and responsibility. People around this person are grieving. How do you treat a story like that, and what are the rules? And there are rules, you know, about whether you can name the person and so on, and I don’t think any of those were followed.

There is a prurience not just with newspapers but with everybody, because you can’t help talking about it. I couldn’t help talking about it. I tried to go away from it, but we didn’t know exactly what happened so it was a mystery. They presented us with a story but people still thought, well did it happen that way? In a way you think what does it matter, because that person is gone. It’s also about protecting our lives and our daughters and what’s left and who’s alive. It’s so complicated. But for months after there was no escaping it, and there was a breathlessness about the way everyone spoke about it.

Another related poem is ‘Disco Biscuits’, about Bill Cosby and Quaaludes and digging up unpleasant memories. How is the #MeToo campaign expressing itself in India? Are actresses speaking up like their Hollywood counterparts? A recent Channel 4 news report showed women confronting sexist and vitriolic internet trolls face-to-face on live TV, which was encouraging.

Yes, there was also something a journalist wrote recently in the New York Times about how she had personally been trolled for a book she wrote about Gujarat. But I can’t remember any major shock in Bollywood, any take-downs. There’s not been any Harvey Weinsteins or Kevin Spaceys, they are still fairly tight-lipped. But in the academic world and in general the power of naming, the power of saying this person did this to me, has had a galvanising effect, and there has been a lot in India about #MeToo. Like in a lot of places, I think we’re in a revolutionary moment, but at the same time I’m not sure that anybody knows what we do with these men, whether we distinguish between a Bill Cosby who feeds people Quaaludes and then rapes them, and somebody who makes a pass and you reject them. We have to figure out again the legislation, the rules. But definitely #MeToo is a catchword and a hashtag that people in India – especially younger people – are quite aware of.

There is a purity or a kind of nobleness in the pursuit of poetry, and I like that, but it also means you have to have alternative things that you do, that’s the deal when you enter it.”

You also write engagingly in this collection about being a poet, from the passion of the calling in ‘Contract’ and ‘Find the Poets’, to its meagre rewards in ‘Clumps of Happiness’ where you picture yourself “swaddling… in stinky sheets” in a budget hotel at a book festival. Do you feel that poets are somehow considered as second-class writers, at least in terms of income?

Martin Amis wrote a short story, ‘Career Move’, where everything was reversed and the poets were flying business class to LA to meet their agents and it was the screenwriters who were in the garrets. It was a lovely imaginary world where the poets were on top. Personally I feel that poetry does offer something that other forms don’t, and people who are involved in it are compelled – in the same way other people are compelled to follow whatever is their artistic calling. But because the money is not so much, I feel that it’s kind of untainted, it’s not questionable. There is a purity or a kind of nobleness in the pursuit of poetry, and I like that, but it also means you have to have alternative things that you do, that’s the deal when you enter it. But there are other wonderful perks, and I do feel that in the community of poets, there’s a generosity that is remarkable, and also the audience for poetry might be small but it’s committed.

You also speak lightheartedly about ageing and mortality in poems like ‘To My First White Hairs’ and ‘The View From Inside My Coffin’. The latter poem responds to a story about how South Koreans are combatting suicide rates with something called ‘coffin therapy’. Can you explain how that’s meant to work?

I read an article on the BBC about how in offices in South Korea they would make employees watch videos of people without limbs or cancer survivors or something, then put them in a coffin with a picture of themselves and close the lid so that they could contemplate the idea of being dead, and then appreciate when they come out how great their life is. It’s a very bizarre concept, and I thought it was just too good and too funny to pass up.

Death is everywhere in this collection, I’m looking at mortality throughout, and it’s normal I think to consider that. In the ageing poems, I suppose it’s a particular time of your life, when you cross 40, there’s a sense of, I was young and now I’m here, and then I’ll be old. It’s a goodbye to youth and a kind of passage.

And how are you coping with that?

It’s great! You know I think it’s a question of finding a graceful way to inhabit that space, and it’s a big preoccupation, particularly for women. It’s this thing of looking a certain way, and seeing past the mad worship of youth that we have in our culture. Personally I like age and wisdom. I like the idea that you’ve lived a long life and you have something to say.

Of course one of your great teachers, your dance tutor Chandralekha, was someone you only met when she was in her 70s.

Yes, I was 26 and she was 73 I think, and it was really wonderful because I didn’t have anyone close to me who was that age until I met her, and it was such a lovely, powerful and intense relationship. I realised there’s this lovely freedom of being able to talk across decades and generations. I like to talk to younger people too, but my natural inclination was always to go up in age, and to be curious about people and what they’ve lived and what they have to say. We have a very strange relationship with ageing, but then in ‘To My White Hairs’ it’s also a tongue-in-cheek thing because you have a certain idea of how you will be, and then when it starts to happen you’re like wait, wait, wait, wait, I’m not ready yet! So I’m aware of that, it’s a catch-22.

‘How To Be Happy in 101 Days’ was commissioned by for the UN Society of Writers for a collection commemorating the International Day of Happiness. Do you think your poem is the kind of thing they were looking for?

Set out into

the world and prepare to be horrified.

Do not close your eyes.

…

If you are attacked, spread your legs and say,

Brother, why are you doing this to me?

‘How to be Happy in 101 Days’

Maybe not, but I’m glad they published it anyway! I got very excited about the idea of it because someone once asked me at a reading, “You don’t have any happy poems, do you?” And so I determined to write a happy poem and it didn’t really work out. Even when I got the job to write a poem about happiness, I started off with very good intentions, and then it went very dark. My point I suppose is that I appreciate happiness as a pursuit, but as a state it’s always in question. It’s also a dig at self-help culture where, you know, if you do x, y and z or buy this, this and that, then you’ll be happy. It’s a shifting emotion. Happiness is something that is never constant and comes in waves. I wrote the poem when I was trekking in Nepal, and all these little stories that are in the poem, like where the Buddha is giving the meat of his legs to the tigress, are actually what the guide was telling me. I just thought it’s so interesting that even religion never really says that you can be happy. You make do with being content, being tolerant.

I think in both that poem and in the wider collection it’s apparent that you’re seeking out joy among the misery.

Yes, and really I do believe that we have to have joy, otherwise how do we cope dealing with the other? It goes together. Life is not pleasant, you’re not living in that Truman Show movie or whatever, that’s a fallacy. You’re human, and this is how it is for us.

How often does it come about that you get commissioned to write a poem? It feels almost like the opposite of poetry.

I’ve been commissioned to write quite a few poems recently and I really enjoy it. Because I’m not in the middle of a project, it’s a nice distraction. Vogue did a book called Dress, where they asked about twenty writers write short stories, essays, and I did a poem. And then for Hay I was asked to write a poem for Armistice Day; they got one poet from each country who sent soldiers to World War I to choose a poem from 1918 and respond with their own poem. So I’ve been reading letters and books, and I’ve been immersed in that history which to be honest I didn’t know that much about, except that India sent a million and a half soldiers. Then the choreographer Wayne McGregor is doing something with the Munich Ballet Company, and for their catalogue instead of having descriptions, they asked different poets to respond to three different works, and I wrote two poems for that. I know there are some purists who believe that poetry should only be when the poem has to come to you independently, but I feel that inspiration is everywhere, and this is like a little intellectual prompt and it’s good because it can take you somewhere unexpected.

There’s a lot of playful structure and varying rhythms in the poems, with rhyming words falling where you wouldn’t necessarily expect them to in the middle of lines. It really suits a poem like ‘What the Sea Brought In’, where a litany of unexpected things comes in on the tide:

Rexine, felt. Rope, mollusk, baleen, foam.

Two ghost children foraging their way

home. The Bootchie Man, budgerigars,

a pack of poor poisoned dogs. Keys,

spoons, singular socks. Virginity returned

in a chastity box. Letters of love,

letters of lust, the 1980s, funeral dust…

‘What the Sea Brought In’

And the whole collection reinforces the fact that poems really come alive when they’re read aloud.

Poetry lends itself to being read aloud much more than fiction. That’s why I put myself geographically where my book is, so that I can do these things, because I think it matters, and I like it. It’s also true that sometimes you have an idea of how a poem should be, and when the poet reads it it’s not quite what you thought, which can be disappointing. But mostly it’s wonderful to hear the poet read his or her own work, because you hear the cadence. Each poem is a universe unto itself, whereas extracting four pages from a 300-page novel and having to contextualise it, unless the writer is an exceptionally good reader I tend to zone out. I would rather have that communion in the privacy of my bedroom where I’m reading. With poetry, both work. It has to work on the page, it has to be something that I can sit on a bench or sit on a bus or whatever and read, but there is also an added pleasure in hearing it performed. When I write, whether it’s fiction or poetry I always read the work aloud, and that is the truest test. If something sounds wrong then I think oh, that’s got to go.

I think creatively as poets we are always borrowing, stealing, jumping off the work of somebody else in one way or another. You read a poem and you are excited to write your own.”

You mention that ‘Strong Men, Riding Horses’ and ‘The Leather of Love’ are Golden Shovel poems. I hadn’t come across the form before. Can you explain how it works?

It’s a new form. Again, these were commissioned. There’s an anthology to honour Gwendolyn Brooks, and the American poet Terrance Hayes devised this structure where you make a poem from a poem. So you take two or three lines from an original poem, and each word becomes the end word of each line of the new poem. So if you read each end word of my poem, it will make the lines from the Gwendolyn Brooks poem. And I liked writing that poem so much, when I was asked to do something for the John Berger book I took ‘The Leather of Love’ from his poem. In that poem I have a line, “I, of limited imagination…” and I think creatively as poets we are always borrowing, stealing, jumping off the work of somebody else in one way or another. You read a poem and you are excited to write your own. There’s no totally original poem.

Can you say something about the dance sequence you’ve devised for ‘Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods’?

I had an idea of some movement for this poem. I’ve never felt like combining the two things before, I’ve just seen them as sharing things like rhythm and time. There are many, many things that feed off between dance and poetry, but I’ve never felt in a literal way like bringing them together until now. Poetry can collaborate with film, with music, because of the compactness of its form, it lends itself to it, but I also think sometimes those other things drown it, and that a poem can stand alone with no back-up noise. But in this case I worked with an Italian friend of mine, a percussionist, who created a score. The poem stands by itself, but this movement and score add another layer to the poem. It’s more performative and also gives it a different power and urgency.

How much time do you currently devote to dancing? Is the Chandralekha Troupe still active?

No it’s not, our last performance was a year and a half or so ago. We had been performing this one piece for fifteen years, and essentially we just came to a stop. I miss it desperately, but the combined age of my dance partner and I was about 87 or something by then, and this piece is particularly demanding. But it’s not a surprise that I choreographed this small, six-minute dance piece when my other dance stopped. While it was there it was such a fulfilling part of my life that I didn’t have the time or the need to do my own thing in that direction. But then there was a sense of oh, I don’t want to not have that.

This is your third collection of poetry and you recently finished a second novel. What stage is that now at?

I’ve just sent an edited draft to Bloomsbury UK, and it will be out in India with Bloomsbury as well. So it’s finished but for a few tweaks and it will probably be published next year.

You’re over here for a full two months. Will you be solely in the UK, or are you travelling around Europe?

I’m going to be here. I’m going to Ireland for a couple of events. I’m doing a combination of things, reading at universities, festivals, doing events here and there mainly in June and also into July. I sublet a place in London and I’m happy to be here enjoying city life because my usual life is quite rural, the coastal life of these poems where there’s that lovely immediacy of the ocean but nothing much else going on in terms of cosmopolitanism. So I’m very happy to be in a city for a time and just to soak up all that it has to offer, see friends, go to plays, go to the museums, walk around. I used to live in London many years ago, so I feel like I know this city and that I am part of it in some way.

I’ve been doing this for many years, where I go on two- or three-month trips away. And this time it will be almost four and a half months. I left at the end of March and was just in America with the book, and when I go back it will be August. Usually it’s not that long, this is an extreme case, but it suits my vagabondish tendencies to be displaced somewhat and to be the traveller, the outsider. I’m happy to have those experiences, and then I’m very, very happy to go home after that. When you work for yourself as a writer you can work anywhere, so I’ll keep working because I have journalism assignments and I have the novel, and there’s a lot of back and forth on that, so I just try to have as regular a writing routine as possible and do my things, and then also try to have fun.

Tishani Doshi is an award-winning poet and dancer of Welsh-Gujarati descent based in Tamil Nadu. She was born in Madras, India, in 1975. She won an Eric Gregory Award for her poetry in 2001. In 2006, she won the All-India Poetry Competition, and her debut collection, Countries of the Body (Aark Arts), won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Her novel The Pleasure Seekers (Bloomsbury, 2010), was longlisted for the Orange Prize and shortlisted for the Hindu Fiction Award, and has been translated into several languages. Her second collection, Everything Begins Elsewhere, was published by Bloodaxe Books in 2012. Her third, Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods (Bloodaxe Books, 2018), is a Poetry Book Society Recommendation.

Tishani Doshi is an award-winning poet and dancer of Welsh-Gujarati descent based in Tamil Nadu. She was born in Madras, India, in 1975. She won an Eric Gregory Award for her poetry in 2001. In 2006, she won the All-India Poetry Competition, and her debut collection, Countries of the Body (Aark Arts), won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Her novel The Pleasure Seekers (Bloomsbury, 2010), was longlisted for the Orange Prize and shortlisted for the Hindu Fiction Award, and has been translated into several languages. Her second collection, Everything Begins Elsewhere, was published by Bloodaxe Books in 2012. Her third, Girls Are Coming Out of the Woods (Bloodaxe Books, 2018), is a Poetry Book Society Recommendation.

Read more

tishanidoshi.com

Author portrait © Carlo Pizzati

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista